Reflow

This is an overview page on reflowing surface-mount components. It is part of our Surface-mount soldering may be easier than you think! series.

Reflow often involves applying solder paste, which consists of little beads of solder suspended in flux, to the pads of the board, placing the components onto the pads, and then heating the assembly to melt the solder creating a joint. There are a variety of ways to apply the paste, and a variety of ways to heat the board. Because of surface tension and other physics, during reflow, parts will “snap” into place even if they were relatively misaligned with the pads.

Tools

Solder paste

Solder paste is made of little beads of solder suspended in flux. There are as many types of solder paste as there are types of solder. There’s lead-free, and 60/40, 63/37, and other mixtures. There’s different types of flux, and ones that have residue that has to be cleaned off boards, and ones that can be cleaned up with water, and ones that don’t need to be cleaned at all.

Some people swear by Kester 256 solder paste. Sparkfun sells both an inexpensive leaded and lead-free solder paste.

As we’ve already said, a lot of the rules and guidelines for SMT soldering are intended for large-scale manufacturing. At this scale, even a few boards needing human attention can add delays and incur extra costs for the manufacturer. When building boards by hand, many of these guidelines can be relaxed or even ignored completely. However, there are some that cannot.

Health and Safety

Solder paste, like solder, has some nasty ingredients in it. This is true of both leaded and lead-free formulations–so it isn’t enough to get the lead out. You don’t want to get it on your skin, and you don’t want to eat it. This is similar to solder wire, however, the particles in solder paste are small, and it can easily get on your fingers or under your fingernails. Many of the chemicals have no biological pathway to exit your body, so they just build up over time. It wouldn’t be a bad idea to wear gloves, but make sure to wash your hands afterwards. There’s even special de-leading soap that isn’t very expensive.

Seriously folks, be careful with your solder paste. You don’t want your child or pet getting into it. Do not store the solder paste in a refrigerator that will ever store food or drinks.

When you’ve finished, clean your tools and work surface. Isopropyl alcohol works well. Don’t throw your waste into the normal garbage can–dispose of it at your local hazardous waste disposal facilities.

Storage

Manufacturers and distributors often store and ship solder paste in a refrigerated environment. They also mark a very short lifetime on their solder paste. While this depends upon the exact formulation of the paste, many hobbyists find that their solder paste works just fine for months unrefrigerated. If you do refrigerate it, do not use one that will ever store food or drink. There are a variety of small, inexpensive Peltier “soda can coolers” that can help extend the life of solderpaste without taking a lot of space. The folks over at Adafruit modded a USB soda can cooler to be powered from a wall-wart.

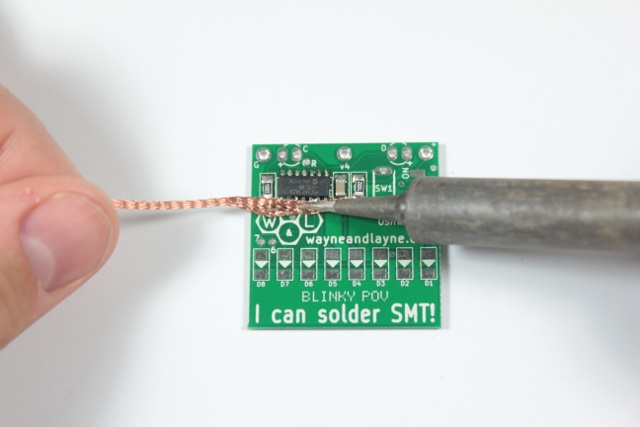

Solder Wick

Solder wick, or desoldering braid, can be used to fix solder bridges. It’s made of thin copper wires braided flat, and sometimes has flux in it. You normally use it with a soldering iron.

Tweezers

Fine tipped tweezers are essential for moving and holding SMT components. We like the ones with the curved tip. You can get decent ones for approximately $6 from our website store.

Some people use vacuum pickup tools to pick up and place components. We don’t.

Magnifier and Light

You’ll want plenty of light when soldering SMT, and you may want some magnification while working. There are good head visors with 2.5x magnification, like the OptiVisors, as well as lamps with built in magnifiers.

When you’re finished working,you may want something like a 10X loupe to check your work. There are even 10X loupes with built-in lighting!

A Stencil

One way to get solder paste on the board is using a stencil. Expensive stencils are made from metal, while cheaper ones are made from plastic. Kapton is a pretty awesome plastic. Ohararp can take board files for a design and laser cut a Kapton stencil for it.

Toaster Oven

Some people use toaster ovens for reflow. Once used for reflow, the oven should be dedicated completely to reflow, and not used for food.

Hot Plate

We (and many other people) really like hot plates for reflow. They are inexpensive (<$30), available locally, and you can easily see what’s going on as it happens.

Reflow Controller

The temperatures and rates at which the board is brought up to temperature, reflowed, and then cooled down is called the “thermal profile“. If you’re making many many boards (or using expensive components), it’s very important to pay very close attention to the thermal profile.

Some people use a reflow controller to control the temperatures of their reflow device. These can be purchased assembled, or as a kit, or you can even try your hand at making your own.

If you’re using something like a hot plate or toaster oven for reflow, and if it’s usually room temperature when you put boards in, we’ve found there isn’t a huge need for a reflow controller. It can’t heat up fast enough to skip the warm-up phase, and it doesn’t cool off fast enough to cause issues. The variability in how long it takes to get to reflow can be controlled by watching the board and turning the heat off when all the joints are reflowed.

Technique

Applying Paste using a Stencil

The basic idea is to use a jig to hold the board on the work surface. This can be purchased or created by using extra PCBs of the same thickness. Lay a stencil over the board, lining up the holes in the stencil with the pads. Tape it down to the jig. Put a small amount of paste from the container onto the top of the stencil. Use an old plastic card or a flexible putty knife to spread the paste across the stencil, smearing it into the hole in the stencil. Check that all the pads have paste on them. The process can tolerate a little inaccuracy here, but hopefully everything is lined up properly. If you need, clean the board with an isopropyl alcohol wipe and try again. Remove the stencil, and the board is ready to be populated. (Remember to safely clean your work surface and tools and dispose of waste appropriately.)

Sparkfun has a short video demonstrating the process. There are many others.

Applying Paste Manually

For most larger package types, you don’t need a stencil. It can speed up making boards, but paste can be applied manually as well. Solder paste can be dispensed manually in a syringe, as well as with something like a toothpick. Hobbyist reflow is forgiving. When applying paste manually, it’s important to remember that while you need to put paste on every pad, you are probably applying too much paste. Most stencils are something like 0.0035 inches thick–think of how little paste that is!

For packages like SOIC, where there are rows of pins, feel free to make a thin line across the row of pads–there’s no need to try to get each pad individually.

Populating Boards with Components

After the pads on the board have solder paste on them, the board must be populated with components. It’s important to have enough light. Use magnification if you need. Some components are polarized and need to be placed in a certain orientation. Check the kit instructions (or the component datasheet) if you aren’t sure.

We use tweezers to populate boards with components, but some people use vacuum pickup tools. These function almost like a gentle solder-sucker, and apply suction to pick up components.

The components should be lined up with the pads as accurately as you can, but the reflow process will line the parts up as long as they’re close.

Check your work! Did you remember to populate the board with all the components? Are they all lined up on the right pads? Are they facing the right direction?

Reflow

After the board is populated, it needs to be reflowed. This involves heating up the solder paste. First, the flux gets liquidy, and the paste spreads out. The solder melts, and the magical dance that you’ve been watching between the pad, the component, and the solder paste culminates. Suddenly, the component lines up with the pad. The first time you see this, you really feel like anything is possible.

While it depends upon the specific solder paste, as soon as all the components have reflowed, it’s ok to turn the heat off. Ideally, no joints are liquid for more than sixty seconds.

It’s important to let the board cool down without jostling it. It’s easy to get excited about your new project, pick it up before it’s cool, and once you realize it’s too hot to touch, drop it the inch you’ve picked it up, and watch all the components shoot off. If you’re lucky, you’ll hear where they bounced off the wall or hit the wall.

Checking your work

Check your work! Do all the joints look properly soldered to the board? Use as much light and magnification as you need. Small bridges can be fixed easily with a soldering iron. Heat up the associated pins and “draw” the solder out. Larger bridges can be fixed easily with solder wick.

Removing Solder with Solder Wick

To use it, put the braid over the joint, and place your iron on top of the braid. The heat (and flux) pulls the solder into the braid. Use the end of the braid, and if it doesn’t seem to be working, first, cut off a small piece of braid from the spool and use that. Depending upon circumstances, the heat may travel up the braid instead of heating up the area on the joint. If the braid is old, the flux may not work. You can add flux to help supercharge the braid.

If you do it right, you’ll see the solder from the board get sucked up into the braid.